How value shapes the fluctuations of conscious perception

What we perceive might sometimes reflect the outcome of a value-based decision-making process, a new analysis of the literature suggests

Although visual perception might seem as easy as just opening our eyes and reporting what is out there, the underlying computations are surprisingly complex. One of the more revealing ways to study these computations is by using inputs that are ambiguous or even impossible under normal circumstances (for instance with radically different pictures seen by the two eyes). Faced with these unreasonable inputs, the brain tends to switch between potential interpretations – where the switching (known as perceptual multistability) obeys some striking rules. Neuroscientists from the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen and the University of Tübingen have assessed a broad literature on aspects of perceptual multistability, suggesting in a paper published in Neuron. They state that it is appropriate to consider switches as internal actions whose choices are determined by forms of internal value (e.g., emotional content of the image).

Max Planck and University of Tübingen scientists Shervin Safavi and Peter Dayan draw on centuries of empirical research and reflection in this field, providing computational and algorithmic interpretations. A venerable idea in the field which comes originally from Helmholtz is that the brain continuously interprets the image on our retinas in terms of the real contents of a scene that might have generated such inputs. This is a computational challenge, since there is an overwhelming wealth of possible contents of the scene; and a statistical challenge, because the inputs from the two eyes from a particular viewpoint only report on a fraction of the actual contents of the 3D visual world. The statistical challenge is only partially mitigated by our ability to move our eyes to look at a different portion of the scene.

The phenomenon of multistable perception

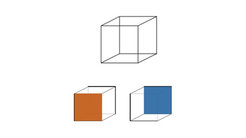

Sometimes, input signals are such that no single interpretation in terms of a particular content of the scene is credible. Safavi and Dayan note famous examples of this, including the Necker cube (a ‘flat’ representation of a solid cube that can be interpreted in two structurally different ways, as pointing left or right). In these cases, our brains then switch between the possible interpretations in characteristic patterns. Although we can sometimes try hard to control our perceptual switches, such conscious processes are often overwhelmed by apparently unconscious ones.

“Multistable perception is a straight-forward and non-invasive way to get a more integrative picture of the link between internal neural operations and conscious reports. We suggest that in case of perceived ambiguity, the brain treats the choice of a dominant interpretation as an internal action, which then, like all other actions, is determined by some form of value. Thus, just as when foraging for food, an animal might successively switch between patches because of the value of the victuals that are available, when processing an image with multiple possible interpretations, we might successively switch between alternative interpretations because of the value that is available from them. Thus, the brain areas, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, believed to be involved in switching between different external behaviours, might equally be involved in switching between different interpretations,” says Shervin Safavi.

Value-based decisions of the brain

What then are the sources of internal value? Examples given by Safavi include aesthetic value – the subjective beauty of an interpretation; and information value – the way that we can benefit from the interpretation in terms of the external actions that we then might need to choose (as in traffic lights); along with special conditions in which particular interpretations are associated with explicit rewards determined by an experimenter.

“Perceptual multistability is a very rich test case for studying neural processing, and so it has been investigated for a very long time, and has given rise to numerous and diverse results. It also has been investigated in context of psychiatric disease, for example schizophrenia, where interpretations can be malformed, and depression and anxiety, where different aspects of value are apparently decreased and increased. We intend to test whether particular aspects of perceptual multistability could be used as a non-invasive tool for understanding psychiatric dysfunction,” Peter Dayan adds.

In sum, the authors hope that their value-based view on perceptual multistability will contribute to a more cohesive understanding of the phenomenon. By involving sensory, decision-making and value-processing systems, it should help neuroscientists paint a clearer picture about what we understand as perceived consciousness, and also provide a new window onto aspects of pathology.